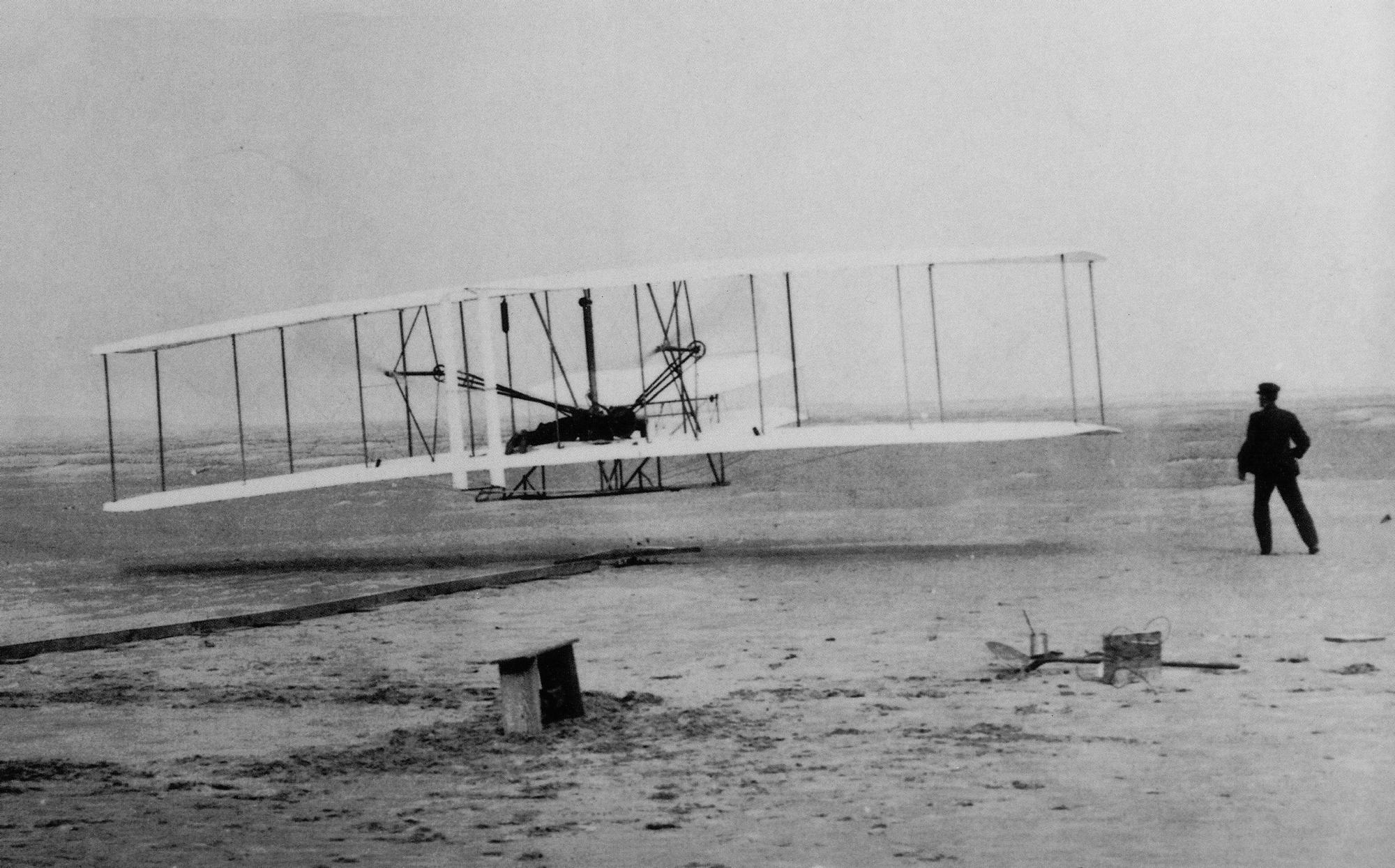

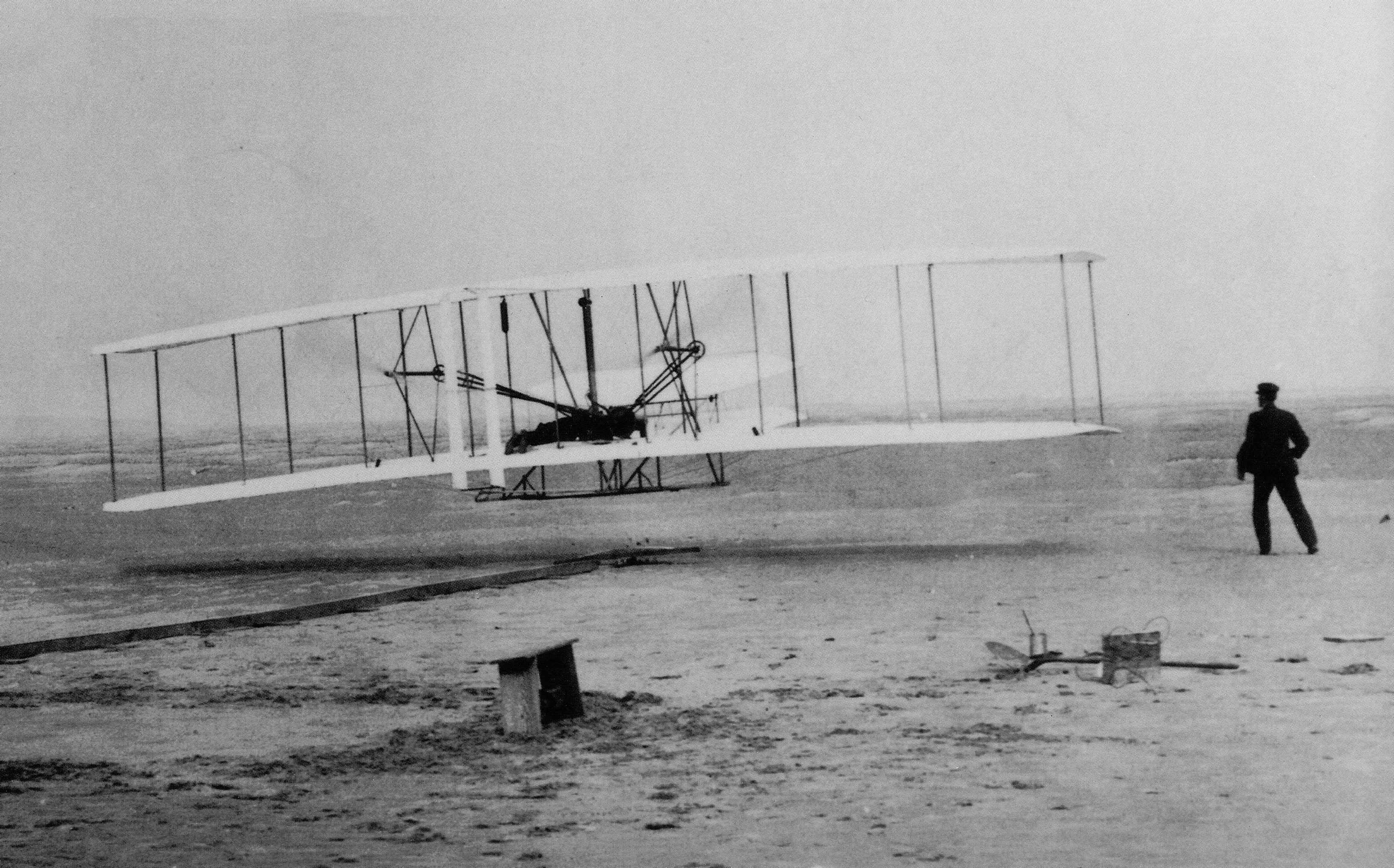

One quick note on December 17th. Back in 1903, this was the day Wilbur and Orville Wright made their first powered flights. They barely held the Wright Flyer of the ground and only managed about 120ft, using a sort of catapult that launched them into the wind. The Boeing 747 — itself over 50yrs old — is actually more than twice as long as the first powered flight. That’s how far and fast we’ve come.

It wasn’t until about two years later, and back home in Dayton, OH, that the Wright’s managed the first practical aeroplane, the Wright Flyer III. That’s when a pilot could actually take off, fly in circles or figure-eights as he pleased, and could stay in the air until fuel was exhausted.

Neither brother was a degree-holding engineer engineer, but they had built printing presses and bicycle components by 1903, and even had several patents for bicycle drive systems. Sadly though, as a business Wright Aeronautical wasn’t successful. They spent so many years suing other companies for copyright infringement that by the time they were settled in court, the patent was for an obsolete technology.

They built an estimated 199 aircraft for public sale, but Wilbur’s health was greatly affected by the years spent in D.C., battling in courtrooms. He died in 1912. Orville never fully recovered from the loss of his brother and partner, and Wright aeronautical was eventually acquired by one of their rivals, Glenn Curtiss.

Curtiss-Wright went on to do a lot though, and the Wright Cyclone engine powered a slew of famous planes. It came in several versions, powering cargo planes like the C-47 Dakota (a few of which still fly commercially as the DC-3 down in South America) and bombers like the famous B-17 Flying Fortress.

The Duplex Cyclone was basically two of these engines Siamesed together, and powered the B-29 Superfortress, which dropped both atomic bombs that eventually ended the Pacific War. Both Charles Lindbergh and Amelia Earhart set records with Wright engines. They even built some early jet engines. In fact, the massive 3,000HP engines in the Martin Mars water bombers are Wright engines.

A plane dear to my heart, they flew as cargo planes and flying hospitals for the USN in WW2 and the Korean War. With the retired planes being purchased by Canadian timber owners, they flew as aerial firefighters until about 2015. I was in Vancouver Island to watch “Hawaii Mars” make its final landing on the waters of Patricia Bay this year, and the sound of those massive engines is a vivid memory.

Hawaii Mars in its firefighting colors being prepared for its final flight, with Philippine Mars behind it, in its US Naval colors. Note the tractor trailers and bus parked nearby to help visualize the scale.

Sadly its sister ship — Philippine Mars — was supposed to be flown down here to be retired at Pima Air & Space Museum in Tuscon, AZ. It made it about an hour before they turned back for low oil pressure in the #2 engine. It was just a pressure regulator problem and the plane was ready in two days. It made it’s second “final flight” but turned back just before landfall in Washington, landing in Patricia Bay with an unknown problem with the #4 engine.

Fair enough though, considering they stopped building these engines in the 1950’s, they’ve been rebuilt multiple times, spent decades flying through smoke and fire while carrying 1,000’s of gallons of water, then sat unused since 2009. Pretty damned impressive for something originally built over 70 years ago and designed over 80 years back.

But the point is, two bicycle mechanics from Dayton, Ohio — sons of a preacher — changed the world with their novel approaches to a question that had been pondered by man for thousands of years: how to slip the surly bonds of Earth and reach out to the heavens.

I’m not saying we shouldn’t be complaining about a lack of legroom or absurd TSA regulations, but the fact that those are our biggest concerns while being shot through the sky, strapped inside an aluminum tube going 650mph, is quite a miracle.

A SpaceX satellite, so high up it is still in daylight, powers its way across the heavens, into the zero-gravity world of outer space.

A SpaceX satellite, so high up it is still in daylight, powers its way across the heavens, into the zero-gravity world of outer space.